Theodore Blegen, in his history of the state of Minnesota, wrote, “Diphtheria was a fearful scourge in pioneer days, especially in the 1880s when epidemics ravaged whole communities.”

Theodore Blegen, in his history of the state of Minnesota, wrote, “Diphtheria was a fearful scourge in pioneer days, especially in the 1880s when epidemics ravaged whole communities.”

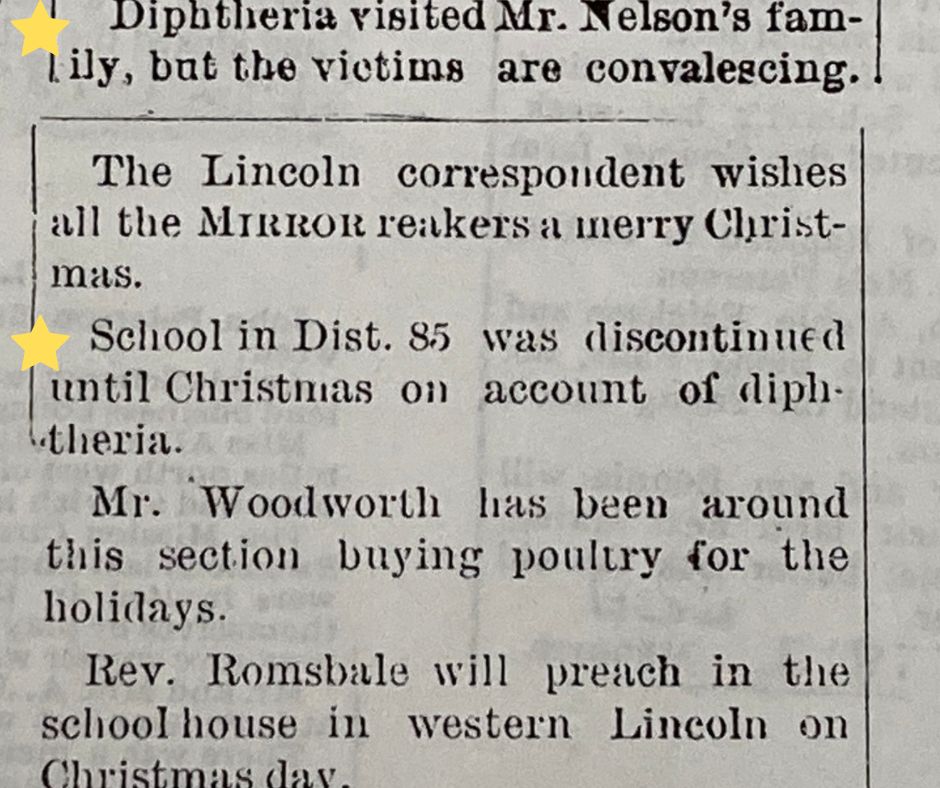

Information on the extent of the various illnesses which affected the residents of Blue Earth County is sparse, and can only be gleaned from the observations prepared by community members and periodically sent to the Mankato Free Press, called “Social Notes.” Along with the notice of births and deaths, there is often mention of illnesses, without giving it a name. It is possible that diseases like diphtheria were more prevalent and more widely spread than newspapers suggest. Later statistics show that there were 49 deaths in the county from diphtheria in 1879, 22 in 1880, and 29 in 1881.

Winnebago City had an especially bad year with diphtheria in late 1879, and Sleepy Eye in mid-1880. In December of 1879, the Free Press published an article from the Windom Reporter that “a lady in Mankato … wrote to her sister here that she could count sixty cases of diphtheria in that city.” The reply, from the editors of the Free Press was “If a lady living in Mankato wrote such a letter, she is no relation to George Washington. The statement is a wicked libel upon our city. The official reporter from the schools in this city shows that there is not a town in this valley freer from diphtheria than Mankato.” The editor, wishing to “set at rest the whole infamous batch of falsehoods and exaggerations set about by evil-disposed persons abroad relative to the health of this city” offered the information that the Mankato public schools showed that 37 students had been sick with some form of sore throat, two of them having died, further assuring the public that “not over half were diphtheria.”

Blue Earth County was not spared in the early 1880s however, especially around Sterling and Mapleton. January 1880 news items acknowledged that there had been numerous cases of diphtheria in the past year in Sterling, but only one case at that time. January 1882 saw the death of a 3-year-old in Mapleton. In February of 1887, the K. Oleson family lost four children to diphtheria in Sterling Township. In September of 1893, two children struggled with the disease in Decoria Township, and in 1900 a little girl died of the fever in Lincoln Township. These are a few of the notices gleaned from the “Social Notes.” However, there are numerous mentions of people improving, or dying, from unnamed illnesses during the same months and years that diphtheria was reported.

Communities and doctors did not know the cause of the illnesses, nor a cure. In mid-December, 1879, when Winnebago City instituted a quarantine of two cities in the county, the Free Press suggested that “the frightened City has made a mistake.” By the end of the month, when Blue Earth City also instituted a quarantine, again the Free Press wrote “We regard these stringent measures as exceedingly injudicious and experience will teach both of those cities a wiser course.”

After a year with several diphtheria cases reported in Sterling, the newspaper noted a debate among doctors about how it was spread. Dr. Francis, of that community, believed that diphtheria was not contagious. Dr. Bishop, of Mapleton, believed that it was contagious, and, according to the writer, “most everyone here thinks it is [contagious].” The writer added, “We would like to hear from the doctors at Mankato.” There undoubtedly would have been conflicting views among those doctors as well. However, by 1891, when diphtheria again made news, the Beauford Social Notes spoke of six deaths in one family, and five in another, and advised that authorities “should endeavor to destroy every vestige of clothing and other articles” of the affected families.” It was even suggested the families should be compensated for their “confiscated effects.”

Diphtheria is a bacterial infection, causing sore throats, fever, and swollen glands. When it progresses toward a fatality, a thick, gray material forms in the back of the throat, blocking the airway so that the patient struggles to breathe. Diphtheria is usually spread between people by direct contact, through the air, or by contaminated items. Children under 15 are the most susceptible, although adults can die from it. Treatment in the 1880s might be broths, gruels, or warm baths. Willow bark could be used to reduce the fever. Dr. F.E. Snow of Mankato advertised a diphtheria preventative in the Free Press, which could be purchased at his drugstore on Front Street. He had developed the medicine, and believed it could also cure diphtheria in children.

Although cases of the disease appeared regularly in the county after the 1880’s quarantines were instituted regularly, which prevented further epidemics. Immunization would not come until the 1920s.

The “Social Notes” also reported on another fever experienced in many communities, a fever with no cure. It was known as “Dakota Fever,” and applied to those settlers who sold their property, left businesses, and move west, looking for better opportunities.

By Hilda Parks

Leave A Comment